A Short History of the Diocese

written by historian, Dr Alicia StLeger

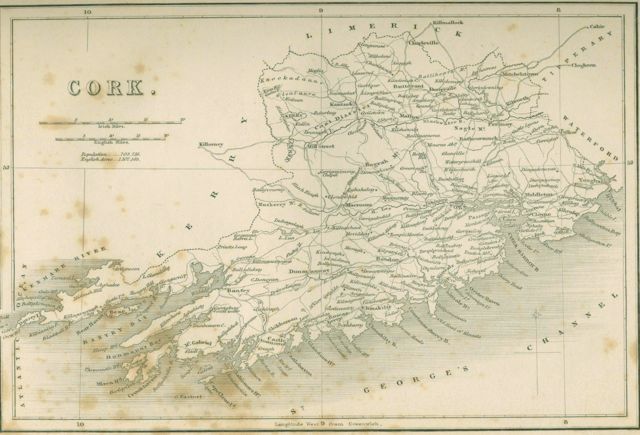

The United Dioceses of Cork, Cloyne and Ross is situated almost entirely within the county of Cork. To the east, portion of the Diocese of Cloyne extends into County Waterford, while in the north-west an area of County Cork belongs to the Dioceses of Ardfert and Aghadoe. Otherwise the diocesan boundaries coincide with the county borders, giving the Dioceses of Cork, Cloyne and Ross a unity that contributes much to its distinctive character.

The Diocese of Cork occupies an area in the centre and west of County Cork, including the city of Cork where Saint Fin Barre’s Cathedral occupies the site of the city’s 7th century monastic foundation. The diocese extends just north of the city and west to the coast. The Diocese of Cloyne occupies the eastern and northern part of the county, with its cathedral (Saint Colman’s) in the town of Cloyne. The smallest diocese is that of Ross which hugs the south coast and has its cathedral (Saint Fachtna’s) in the town of Rosscarbery. The Diocese of Ross originally included part of the Beara peninsula, but following parish re-organisation in 2000 this portion is now part of the Diocese of Cork.

Map of County Cork from Mr. and Mrs. S.C. Hall’s ‘Ireland: its Scenery, Character etc.’, Vol.I, 184.

The three dioceses have been united since 1835, providing an element of stability that has assisted in the development and administration of the United Dioceses. However, they were not always united. The Diocese of Cork grew out of the monastery that was established in the 7th century in what later became Cork city. Created as part of the structural reorganisation of the Irish Church at the Synod of Rathbreasil in 1111, the Diocese of Cork initially extended from Cork to Mizen Head and from the River Blackwater to the ocean. This territory later was reduced by the emergence of other dioceses.

The Diocese of Ross was created by the Synod of Kells-Mellifont in 1152 and was based on territory then controlled by the O’Driscolls. In 1583 it was united to the Diocese of Cork. The then Bishop of Ross, William Lyon, had been appointed in 1582 and in 1583 he also became Bishop of Cork and Cloyne. The Diocese of Ross has been united with Cork since that date.

The relationship between the Diocese of Cloyne and those of Cork and Ross is more complex. The Diocese of Cloyne was created after the Synod of Rathbreasil (1111), taking lands formerly held by the dioceses of Emly, Cork and Lismore, and was recognised at the Synod of Kells-Mellifont in 1152. It was an independent diocese until 1429 when it was united with the Diocese of Cork until 1638. Following the episcopate of George Synge, Cloyne was again united to Cork and Ross for a short period from 1661 until 1678. In 1679 a Bishop of Cloyne was again appointed and the diocese remained separate until 1835 when it joined Cork and Ross. Since that date Cloyne has been part of the United Dioceses of Cork, Cloyne and Ross.

The close correlation of the diocesan boundaries with those of the County of Cork has strengthened the sense of identity in the united dioceses. There is a strong feeling of ‘family’ in the dioceses. This has been helped by the pre-eminence of the city of Cork in terms of size and geographical location. With just one major city in the dioceses, in which the Bishop resides, it is a natural focus for certain diocesan and civic occasions. The result is that the representative role of the bishop is larger in civic affairs compared to other dioceses. The Bishop lives in the elegant Bishop’s Palace (1782) opposite Saint Fin Barre’s Cathedral, thus providing the feeling of a ‘close’ on an ancient site in the city centre. Although the role of the city is very significant in the dioceses, the strength of the county is equally important. The strong role of the Church of Ireland population in the county is reflected in the historic spread of churches and the strength of many parishes.

Whether city or county based, the united dioceses has been fortunate in the active involvement of many men and women in the local and national affairs of the church. Until the early twentieth century, the landed families played a significant role in the life of the church and, indeed, provided many of the clergy who worked in the dioceses and further afield. The disturbed political period from 1919 until the mid-1920s had a particularly significant impact on the dioceses, since the county was one of the main centres of fighting and intimidation. During the worst years, many members of the Church of Ireland (both lay and clergy) left the county. The political climate of the new regime and fears for the future meant that some never returned. By the mid-twentieth century, the traditional strength of the landed families had greatly declined. However, the tenant farmers, who were particularly strong in west Cork, tended to remain on their lands. Although affected by emigration and suffering many difficulties during the War of Independence, they and their descendants remain an important part of the Church of Ireland community.

Change also occurred in the city parishes from the early twentieth century onwards. There was a gradual decline in the working class and lower middle-class Church of Ireland community. This was partly because of political unrest and emigration, but also reflected a sustained movement out to more middle-class suburbs such as Douglas. By the mid-twentieth century, city churches saw declining numbers and over the following half century many were closed. By the early twenty-first century only Saint Fin Barre’s Cathedral and Saint Anne’s Church (Shandon) remain in the city centre. Similarly, city centre Church of Ireland schools underwent a process of closure and amalgamation. This phenomena is not unique to Cork, but reflects changes in wider society.